Los metafísicos de Tlön no buscan la verdad, ni siquiera la verosimilitud : buscan el asombro.

J. L. Borges

If I am dissatisfied with André Bazin’s definition of neorealism, I can at least say this for it: that it lays bare, to my eyes, that I do not really know what realism is in the first place. An easier exercise than defining realism is to name things that are not realist: Yellow Submarine, with its Blue Meanies, its Sea of Holes, and the high-on-acid visual carnival that is its driving principle, is not realist. Beyond this rather obvious, even demarcating point, however, even naming nonrealist things becomes difficult. Star Wars seems nonrealist, what with Wookies and Ewoks and whatnot, but the existence of such a thing as magical realism calls even this categorization into question. Realism is not defined, it would seem, by the presence of the objects of reality (or the absence of unreal objects) in some or another realist work, but by the re-creation in the work of the nature of reality—whatever that means in media other than painting, where realism has an immediate and obvious significance: the things in a painting can look more or less like things do in real life (or, to use a more precise phrase for it, the physical world): a painting can be more, or less, distinguishable from a photograph.

A definition of realism as photorealism transposes nicely onto animated films, but how can it transpose onto live-action films? A live-action film is a series of photographs. The critic setting out to define filmic realism faces the opposite problem as the critic setting out to define literary realism: film seems, already, too real. Sure, there are special effects: the viewer of All About Eve is treated to a nonrealist experience when she watches Eve and Addison stroll through an obviously projected New Haven. But special effects have only gotten more special since 1950, and such obvious moments of movie magic are a rarity nowadays. If filmic realism is merely the recreation of the visual style of reality (and let us suppose for the moment that such a style exists, on a know-it-when-you-see-it basis: Le Bonheur looks more like reality than All About Eve’s New Haven walking two shot, which looks more like reality than Yellow Submarine), then virtually every mainstream movie made today—the exceptions being such fare as movie musicals and the work of Wes Anderson—is realist, including, thanks to advances in computer-generated imaging technology, the most recent Star Wars instalments.

The problem of defining filmic realism is deepened by the fact that realism is not used as a strictly stylistic term and does, even in painting, relate to content. Realist works are about the gritty elements of life that other art works to ignore or obscure. A nonrealist war movie might depict war as a glorious and ideological struggle for truth, justice, and the American way: a realist war film will show its audience what gangrene looks like. (It is not coincidental that movie seems like the most appropriate term in the first case and film in the second.) There is, as this example suggests, a political dimension to this view of realism, since the myths that realism sets out to refute tend to be those of the reigning political system, such as the myth that the Old West was a land of rough-hewn and noble individualists—or the rather curious myth that labor does not happen, which is why realism is so prone to depicting such productive mundanities as construction workers laying bricks and Jeanne Dielman peeling potatoes. In other words: the reality that realism embraces is defined, in part, negatively: it is not simply the world as it is but the world as the Powers That Be would have you think it is not.

All of which is of limited relatedness to Mr. Bazin’s definition, which he borrows in part from Amédée Ayfre. Here’s Bazin: “in the first place [neorealism] stands in opposition to the traditional dramatic systems and also to the various other known kinds of realism in literature and film with which we are familiar, through its claim that there is a certain ‘wholeness’ to reality.” The first part of this definition corresponds nicely to our contention that realism is defined negatively: “traditional dramatic systems” are unreal, so realism rebels against them. The second part accounts for the neo in neorealism: (non-neo) realism regards reality as basically fragmentary, whereas neorealism regards it as unified. Mr. Bazin and Mr. Ayfre usefully identify a metaphysical difference between realism and its neo’d successor, at least as they define the two, with neorealism taking an almost monotheistic view of reality as having an essential Oneness.

The difference is aesthetic in addition to metaphysical. In the essay that Bazin cites, Ayfre describes how Dziga Vertov sought to depict reality by simply going out and filming stuff, an approach Ayfre regards as embodying the documentarian view of the world. Vertov concluded, however, that in order to turn his collection of his snippets into a film, to make them more than “a document of primary importance to the town planner or the sociologist, but of no great interest for those concerned with art,” he had to edit them together with a certain rhythm, the concern with which rhythm led him straight from “the rawest kind of realism … back into abstract art.” Montage might seem to be incompatible with realism, since reality does not after all come in edited-together pieces. By definition, montage involves artifice. But reality also does not come from a single point of view at a time, as movies necessarily do. If realism implies a lack of artifice, then realism in art is a contradiction at terms. And maybe it is—but our goal, surely, should be to find a stable definition of the thing. At all events, in Ayfre’s account, it doesn’t so much matter if montage (perhaps especially rhythmic montage) is real or not: it is necessary to the seventh art’s artisticness, and if true realism would require its abandonment, then fie on true realism! (Besides, apparently one-shot movies like Rope or 1917, because they depart from the convention of montage, call attention to their own craft; if, on some theoretical level, realist film is film without montage, montage is by now so ingrained in what audiences expect from a moviegoing experience that realist film has simply become an impossibility.)

All this has a whiff of balderdash, no? Bazin has the decency to situate his discussion in the context of Journey to Italy; Ayfre, rather more concretely, takes as his object Germania anno zero. Let us now take up Roma città aperta, by reputation (which is most of what matters when it comes to working through generic assignments) a neorealist film if ever there was one. In several respects Roma città aperta seems like a strange posterchild for realism of any kind. Yes, it is gritty, but so are the cartoonish films of Quentin Tarantino, a master of nonrealism. Its characters are proletarian, true—yet its scenario is not concerned with their day-to-day mundanities but with their liberationist plotting and actions. There is the one scene in which The People, including Pina, riot rather modestly for their bread—but it serves to underline the intolerable character of the out-of-the-usual Nazi occupation rather than the reality of urban poverty under capitalism. Does Roma città aperta defy traditional dramatic forms? It has an explicit two-act structure. Each act ends in tragic martyrdom. There is exposition, rising action, a climax, and a brief dénouement. There are evil Germans and heroic Italians, and while the former win the battle, the latter show that it is their own fighting spirit that will cause them to win the war.

None of which is to denounce Roma as oversimple or twee; but there is not much in it that challenges narrative as such: it is no Jeanne Dielman, nor is it even a Paisà or a Journey to Italy—which may have something to do with what Bazin means when he writes of the “wholeness” of reality as seen by neorealism. The idea that reality exists independent from human experience is a dubious proposition in the first place, and its relevance to the sphere of the artistic, this sphere being one of human creation and perception, is more dubious still. Perhaps, then, what realism ought to aspire to is not the rendering of such an independent reality but the rendering of reality as it is actually seen by some or another auteur. Bazin claims that neorealism “looks on reality as a whole” because individuals perceive reality as a whole rather than as a series of significations (hence the lack in neorealist films of stagelike acting that “presupposes on the part of the actor a psychological analysis of the emotions to which a character is subject and a set of expressive physical signs that symbolize a whole range of moral categories”), and the goal of the neorealist auteur is to understand how she herself perceives reality and to render that perception on film.

Which is destabilizing in two main respects: first, because it introduces into the mix something we might call “impressionist realism,” which seems like an oxymoron, and second, because it discards altogether the importance of content to neorealism. “Neorealism contrasts with the realist aesthetics that preceded it,” Bazin writes, “in that its realism is not so much concerned with the choice of subject as with a particular way of regarding things”—a strike from Bazin against the popular consensus view of neorealism, which, if we may take Wikipedia to represent it, emphasizes that neorealist films “primarily address the difficult economic and moral conditions of post-World War II Italy, representing changes in the Italian psyche and conditions of everyday life, including poverty, oppression, injustice and desperation” and makes absolutely no reference to a creative spirit that is both elliptical and synthetic.

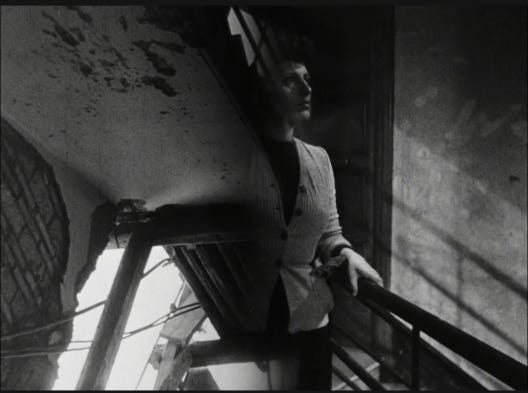

Let us set aside the question of “impressionist realism,” which can lead us only too easily into a dialectic circle surrounding the possibility of true knowledge. No one can have certainty of anything other than their own existence, true, but there is also a clear difference between Yellow Submarine and Paisà. Capiche? We might get more out of taking on the second problem, of whether neorealism is basically a stylistic or substantial phenomenon. Consider the penultimate sequence of Roma città aperta’s first act (for all intents and purposes its final sequence, since what follows is an epilogic scene in which Francesco is rescued from German captivity): Pina’s moment of martyrdom and what leads up to it. The most obviously realist piece of the sequence—that is, the one that seems most to call upon us to point at it and say: “Behold, a realism!”—is the shot in which Pina is actually shot down. It seems realist both because of its brutal subject matter and because of its formal shakiness, which lends it a documentarian feel. Yet the sequenc eas a whole is highly edited: from the moment Pina first cries out to Francesco to the moment she dies, the average shot length is 2.43 seconds. And these shots are carefully chosen, the editors cutting carefully back and forth between Pina, Francesco, and Marcello as Pina runs to her death, while not only does the camera crew know where to situate itself to prepare for Francesco’s entrance, we even briefly get a side-view tracking shot of Pina running toward the truck—a highly un-documentarian device with great emotional impact.

All this montage, which upon analysis reveals itself to be artificial and deliberate, serves to speed up the pace of the action and make Pina’s death feel more abrupt—as such a death, unpremeditated, in the streets, wrought by highly efficient gunfire, surely feels in real life. Had Rossellini shot the entire sequence with a deep-focus wide-angle long take, it might have been more authentically documentarian—but it might also have felt falser, and less in line with Rossellini’s reality.

Still—is her death not a little idealized? It’s brutal, sure, but it’s also a kind of martyrdom. Pina is a symbol of modern female virtue, defined not by her sexual chastity or her forgiving spirit but by her fearless and noble moral character. She has some doubts about the rectitude of marrying in a church while pregnant, but her doubts are misplaced, as Don Pietro seems to understand. He is an ideal, too: a Christian who does not really care about sexual purity, who might prefer that Pina and Francesco not have premarital sex but understands that what really matters about them is their participation in the resistance against the Nazi occupation. Major Bergmann tries to goad Don Pietro by reminding him that the left and the Church are traditional enemies, but Don Pietro won’t have it. In Roma città aperta, atheists and Christians stand together in the defense of humanity, their respective moral commitments are boiled down—to a secular one. Don Pietro’s belief that Jesus of Nazareth is the Son of God and the Word made flesh is made incidental. Is this a realist vision of the world or an idealized atheistic one?

The distinction is meaningless, if we persist in sidelining the paradox of “impressionist realism” and allow that what we might label secular idealism is just how Roberto Rossellini understands reality—but then we might have to ask ourselves if the world of Top Gun: Maverick is simply Joseph Kosinski’s reality. Might not that film or any dime-a-dozen Western be said, as Bazin claims of Journey to Italy, to depict “a mental landscape at once as objective as a straight photograph and as subjective as pure consciousness?” Perhaps the distinction lies in this: Kosinski’s characters fly planes, literally lift themselves off the ground, to achieve some kind of higher level of existence. But Rossellini takes as the essential material for Pina’s martyrdom the running of a woman down a street—which jibes well with Bazin’s assertion that “Rossellini directs facts … Gesture, change, physical movement constitute for Rossellini the essence of human reality.”

This may be why Roma città aperta certainly feels more real than Top Gun: Maverick. Let us not be disingenuous, and let us state our case clearly: We know what people mean when they describe Roma città aperta and its ilk as “neorealist,” in the sense that we also feel it to be true that it is, somehow, more realist than Maverick. But we struggle to understand why, and we feel that Mr. Bazin’s contribution to our struggle, great though it may be, is incomplete.

Part of what makes Pina’s death, when it comes, so striking is that what leads up to it is the essentially farcical scene in which Don Pietro and Marcello retrieve and hide Roberto’s weapons, then pretend to be reciting the last rites for the paralyzed old man. True, this is farce; and true, it is a suspenseful sequence the suspense of which is heightened by such clearly deliberate techniques as the cross-cutting between tracking shots of Don Pietro and Marcello climbing the stairs and stationary birds-eye view shots of the Nazis pursuing them. But it is also a piece of realism: sometimes reality is farcical. There would be something annoyingly pat in the sequence if one felt that through it Rossellini was attempting to persuade one of a message: “You see, movements live and die on such actions! A Priest and a child improvisationally knocking out an old man with a frying man—this, not the heroic gunfire of muscular men in pseudo-uniform, is the stuff of resistance to Naziism!” In part precisely because Rossellini lathers the sequence is suspense, it does not have such a didactic effect, its chief character being dramo-comedic. There is potential for didacticism, too, in the juxtaposition of Don Pietro and Marcello’s farce with Pina’s tragedy. “Ah, life: comedy and tragedy, side by side. Such is the dual nature of the world!”—the film could say this but doesn’t. That duality is simply part of the reality of Rossellini’s world. As Bazin says, it is “neither psychological nor logical: it is ontological.” That is not to say that Rossellini the historical individual did not think about psychology while making the film, or that logical consideration of metaphysics did not inform his thinking of it; only that the film itself does not engage in such analysis and, even if it is possible for us to conduct such analysis, does not invite it. The juxtaposition of farce and tragedy just is, and its main effect is not analytic but dramatic: Pina’s death is a gut-punch. The realism of the sequence is evident in the degree of its emotional impact, and in the fact that the sequence has a similar emotional impact upon rewatch and after critical consideration. Is the use of montage in Pina’s last moments manipulative? Perhaps: we can identify how the editors use brief shots to make us feel the action is sudden; we can identify how they choose to cut to characters whose appearance will most tug at our heartstrings. Yet the fact of this manipulation, if it is proper to call it that, is of little evaluative significance: all art is deliberately constructed, most art is designed to have an emotional relationship with its viewer, and the noting the techniques used in Pina’s death sequence does not vacate the sequence of emotional content.

The English title of Roma città aperta, a quite literal translation from the Italian, is Rome Open City (sometimes rendered with a comma after Rome), so: how is Rome open, and to whom? Rossellini’s Rome is a city open to the Nazis, for starters, who have in turn closed it by sharply constricting its denizens’ freedom. Its inhabitants hope that it will soon be open to the Americans, though they are skeptical that this will ever happen (and besides, Rossellini himself will, in faithful realist fashion, shatter the myth of an uncomplicated liberation of Italy just a year later in Paisà). Visually, Roma città aperta begins with a series of pivots from openness to closedness: we start with a daytime view of the Roman skyline, an open image, but the moment the credits have ended, we begin hearing a group of men singing in German to the steady beat of marching bootsteps. Our assumption that these men are Nazi soldiers is immediately confirmed as we cut to them, now in a nighttime sequence of such darkness as to render them barely visible. Now the plot begins: a middle-aged man, handsome and hardy, beats a narrow escape from the Gestapo. His mechanism of escape is to climb over rooftops to safety, to make Rome open itself up to him. It is dark outside but there seems to be light coming from the horizon: the day may be dawning from the night, and this man may be dawning into the safety from the near-clutches of the Nazis, and the movie is certainly dawning on us.

The literal, optical mechanisms of brightness and darkness may reinforce whatever metaphoric associations we might hold between light and openness on the one hand and dark and closedness on the other: the eye, and the camera lens, must open up to let in light; a projector must open to let it out. The link between German occupation, closedness, darkness, and evil is so in-your-face as to avoid didacticism: like the juxtaposition of farce and tragedy at the close of the first act, it is just a fact of Rossellini’s reality. The sun is not symbolic of goodness; only the two are linked; they just are. There is an optimistic current to the film’s end, despite the fact that Pina, Don Pietro, and Manfredi have been killed while Francesco’s fate remains uncertain, because the film ends as it began, with the Roman landscape in broad daylight, exposed to the Nazis, yes, but also certain to triumph in the end. This, in addition to how their deaths are shot—Pina a perfect pieta, Don Pietro the center of an astounding landscape, Manfredi an atheist’s Christ—lets the film’s casualties function as martyrs. One need not believe that martyrs exist in one’s own real life to accept their possibility in the life of the film, their existence as a feature of its landscape.

Perhaps Rossellini himself believed in martyrdom; perhaps he did not. It may be beside the point. One of the more intriguing passages in Bazin’s essay is the one in which he constructs an elaborate metaphor comparing the different forms of realism to different ways to get across a river. Traditional realism, in his metaphor, is like an arched bridge. One knows the bricks that make up an arched bridge by their intrinsic composition. The keystone of an arched bridge is a keystone, to use Bazin’s phrase, a priori to its insertion into the bridge structure. It can only be a keystone. In this same way, a highly detailed and thus vivid description of a bureau in a novel might mark itself, in isolation, as an element of a realist work. A person reading about the bureau sees it so clearly in her mind’s eye that, to her, it might as well exist in the physical world, and thus she knows: “This novel is reconstructing reality.” (Is literary realism of a visual stripe then simply nonexistent to aphantastics?). A viewer of Citizen Kane might see the deep focus in the scene where Thatcher first picks up little Charles and think: “Aha, Welles has captured all of reality in this scene, as it really is.” There are, it is true, some such moments in Roma città aperta, as when, during the soccer game at the church, the camera follows the boys as though in a documentary. The shakiness of the camera when Pina dies has a similar effect. But, for the most part, Roma città aperta—and, Bazin says, neorealist films generally—is not realist in that its constituent parts each embody realism; it does not resemble an arched bridge. Instead, it resembles “the big rocks that lie scattered in a ford,” or rather its constituent parts do: there may be no one shot in Roma città aperta that marks it as decidedly realist. Roma città aperta is realist because of how all the shots in it are edited together. It becomes realist as one watches it, in the same way that rocks in a ford become a bridge of sorts when one “leaps from one to another … to cross the river,” bringing one’s own “share of ingenuity to bear on their chance arrangement”—which is why neorealist is an appropriate designation for the film. Thus we come back to “impressionist realism:” as I understand Bazin’s metaphor, neorealism might also be compared to a pointillist painting. Any individual dot in Un dimanche après-midi does not bear the mark of reality, but the act of looking at the painting as a whole lends it a verisimilitude.

I devote so much space here to unraveling Bazin’s metaphor because it confuses me. And just as I seem to have alit on a sensible interpretation of it, he throws me another curve ball: “If my analysis is correct, it follows that the term neorealism should never be used as a noun, except to designate neorealist directors. … I will only deny the qualification neorealist to the director who, to persuade me, puts asunder what reality has joined together.” This is consistent with Bazin’s claim that “the traditional [that is, non-neo-]realist artist analyzes reality into parts which he then reassembles,” but what about directors who are simply not realists, neo- or otherwise? Do they all sunder reality along with the traditional realists? Bazin claims that he lacks “enough of a head for theory;” we would certainly tremble to see what a writer with enough of a head for theory should look like, since it strikes us that Bazin produces a great number of principles that are only rarely explicitly tied down to specific works of art and are otherwise of highly opaque application to concrete aesthetic artifacts. Alright, so Rossellini communicates a unity of reality, as filtered through his own subjective consciousness, whereas traditional realism would analyze reality and nonrealism would—what? Edge cases are highly useful in understanding categorizations, but we struggle to name ones beyond the likes of Yellow Submarine. Even something like Le Charme discret de la bourgeoisie, surely not a neorealist work if the term “neorealist” has any meaning at all, could be said to communicate a director’s unified vision of reality.

We are, perhaps, being too hard on Bazin. If the present essay proves anything, it is that theory is difficult, and his essay has a very specific context: He is defending Rossellini, apparently against accusations that Rossellini had abandoned or betrayed neorealism with Journey to Italy. Since no one was accusing Rossellini as having betrayed neorealism with Roma città aperta, widely known as one of the works that kicked off the neorealist movement in the first place, Bazin did not set out to acquit him of that charge or to explain what made Roma città aperta neorealist. Ayfre gets closer to this task in “Neorealism and Phenomenology,” but the comparison is still always between neorealism and traditional realism. Occasionally we get a distinction like: “reason and thesis play no part [in neorealism, but] there are always awareness and involvement. Social polemic there is, but not propaganda,” whereas in traditional realism there is a claim to objectivity. Ayfre emphasizes that the settings of neorealist films are not décor, that they are simply a part of the film, just like the main character is—perhaps, then, we might say that Good Will Hunting is not realist because it cannot be said that Boston in that film “‘exists’ almost on the same level as” Matt Damon, which is how Ayfre describes the relationship of the world of Landri di biciclette to that film’s protagonist.

Good Will Hunting is a useful example because it is not actively surrealist. Yet even setting aside the fact that the film revolves around a perhaps less-than-realistic supergenius we might resist labeling it realist in the same way that Roma città aperta is realist. Certainly our own instincts—which, for the moment, are still really the most solid thing we have to rest upon—will not allow for that label. So why? We have accounted for the neo in Roma città aperta’s neorealism by contrasting it with traditional realism: now let us account, finally, for the realism. Why are the Nazis singing “Märkische Heide” in the film’s opening more than décor? How do they differ from the Bunker Hill Community College students of Good Will Hunting? Perhaps “Märkische Heide” is particularly humanizing song—not to say that the film makes us feel sorry for the Nazis (it never does), but they are nonetheless, right out of the gate, more fully realized than Robin Williams’s lazy, gum-chewing pupils. Although their function in the film certainly will be to play the part of villains, their existence precedes this essence. In this light, the shaky-camera documentarian aspect of the soccer game takes on a new significance: not that it tricks the viewer into thinking they are watching a documentary, but it grants the soccer game existence. Had the soccer game been filmed at a remove, it would feel décorous, to coin a solecism; filming it up close makes it feel as much a part of the world of the movie as Pina’s death—which, in turn, lends Pina’s death that much more of a feeling of realness, since it is, to use Ayfre’s phrase, “surrounded by a bloc of reality.” Such clear tricks as the use of montage to make it look as though Don Pietro accidentally effects a header in that game, rather than stripping away the film’s sense of reality—already quite stripped away enough by the fact that we are watching it in a dark room on a flat screen—unite the protagonist Don Pietro’s reality with that of the soccer game.

It is possible to quibble with Rossellini’s claim to realism, as we have now defined it. We are struck by how Giovanna Galletti’s appearance marks her as sinister the moment she comes onscreen: She is tall, she has a wide jaw, her cheekbones and lips are sharply accentuated. Her existence does not precede her essence, a cheap trick on Rossellini’s part the apparent purpose of which is to make us feel sorry later on that Marina—shallow, frivolous Marina—has been ensnared by Ingrid’s Sappho-Teutonic intrigue. The problem of the film’s portrayal of gender—there is virtuous Pina, martyred by the Nazis; selfish Marina and Lauretta, shallow and therefore useful to the Nazis; and evil, masculine, sensual Ingrid—is not so much that it fails to reflect reality as we noble feminists experience it or that it threatens propagandistically to make patriarchy ascendent in this our “real life.” The problem, from a neorealist standpoint, is that it turns variations on femininity into signs. The film starts to analyze itself without, however, rising to the analytic level of the best traditional realism, reliant as its analysis is on the crutch of sexism. In good traditional realism, the fact that a component part of reality is to be analyzed does not reduce it. The dim constellation of womanhood in Roma città aperta, in contrast, serves to reduce some of its women to décor. The problem is not quite so bad here as it is in Good Will Hunting, but it is still there.

Nonetheless, Roma città aperta is generally a quite unified picture, in a way that Good Will Hunting is not. Almost everything and everyone in Roma città aperta seems to occupy the same level of existence, in Ayfre’s formulation, even if the techniques used to make this so are clear upon analysis or even upon raw viewing. Our distinction will hold up, too, if we compare Roma città aperta to a better film than Good Will Hunting, say, Le Charme discret. One of the major apparent incompleteness of Bazin’s definition of neorealism is that unity in art is simply a general aesthetic criterion. And, yes, Le Charme discret has a definition unity of artistic vision; but part of that unity is the constant sundering of the film’s reality. The constant cutting in that film to the protagonists walking down a road does more than remind us we are watching a movie (which fact is, usually, pretty hard to forget in any case): it fractures the world of the film itself, disturbs its wholeness.

There is an odd moment, near the beginning of Roma città aperta, in which Pina asks Marcello to come down from the roof of the building to go fetch Don Pietro. After resisting a little, he comes down, and then we get a wipe transition to—his reaching the bottom of the staircase. It is a short staircase: it is entirely possible that the wipe transition covers no time at all. The juxtaposition it creates is not of obvious thematic significance and constitutes another of the film’s “openings:” by using a transition usually reserved for traverses over expanses of time or space, Rossellini makes us feel as though much time has passed between when Marcello begins to descend the stairs and when he reaches the bottom. This is neither realist nor neorealist: without approaching the absurdist heights of Le Charme discret, it creates a nondiegetic fissure in the film’s reality, a sort of cinematic wormhole. Thus, even after we have labored to define neorealist so as to include the early works of Rossellini, we find that Roma città aperta does not perfect fit our generic bill.

This is as it should be: every film, or at least every great film, is unique, and ought to resist generic assignment. What we may take as significant, for now, is that Roma città aperta is not defined by such moments as this odd wipe transition. For the most part, its center holds, all the while being driven by a decisive and openly subjective artistic vision—such open subjectivity being necessary to create anything like Manfredi’s final nod, which is crucial to the film’s project. Neorealism (or, to sate Bazin, “the neorealist approach”) allows Rossellini to depict the world as he sees it, to let us experience it this way, without having to turn himself into the philosopher-artist. Not that we have anything against the philosopher artist; but to the artist not naturally inclined to that role, the demands of philosophy can be straining; just as the demands of theoretical exactitude can leave the instinctively humanist essayist exhausted and not a little bewildered.

This essay was originally written for Tom Conley’s “Landscapes of Cinema” course, conducted at Harvard University in the Fall of 2022. To Prof. Conley, my thanks.